Chuck Close American, 1940-2021

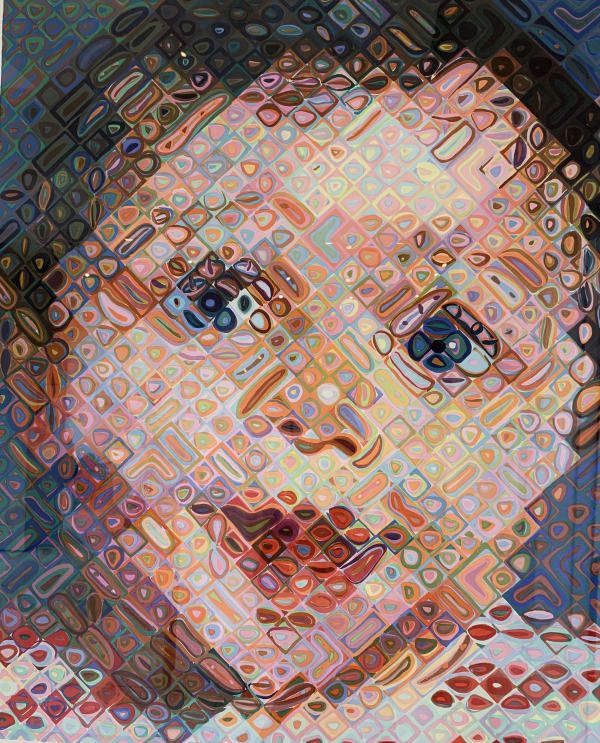

Chuck Close’s prominence and popularity are due mostly to his photographs and the giant portraits he has painted since the 1960s. Based on photographs, the portraits are monumental close-ups of heads (his family and friends) produced under various limitations (some self-imposed creative techniques, some health-related).

In a 1997 interview, Close told New York Times reporter, Michael Kimmelman, “My (early) learning disabilities also affected what I did as an artist. I could never remember faces, and I’m sure I was driven toward portraits because of the need to scan, study and commit to memory the faces of people who matter to me. The other thing is that I’ve always been incredibly indecisive and overwhelmed by problems, and I’ve learned that breaking them down helps, which is exactly how I paint a portrait: I break it down into bite-size pieces, into lots of little manageable decisions... What moves me about Seurat’s art is the incremental, nuanced, part-to-whole way his paintings are built out of elegant little dots, though I feel even more of a kinship with Roman mosaics because the mosaics are made out of big, clunky chunks, and I especially like the idea that something can be made out of something else so different and unlikely. In Roman mosaics, an eyeball is made from the exact same chunk of stone as the background, and this brings up the concept of all-overness and Jackson Pollock. It’s what I aim for in my own work, an all-overness that’s different from what most portraitists do by putting all of their attention into the eyes, nose and mouth.” (“At the Met with Chuck Close,” The New York Times, July 25, 1997, p. B22.)

The remarkable career of artist Chuck Close extends beyond his completed works of art. More than just a painter, photographer, and printmaker, Close is a builder who, in his words, builds "painting experiences for the viewer." Highly renowned as a painter, Close is also a master printmaker, who has, over the course of more than 30 years, pushed the boundaries of traditional printmaking in remarkable ways. Almost all of Close's work is based on the use of a grid as an underlying basis for the representation of an image. This simple but surprisingly versatile structure provides the means for "a creative process that could be interrupted repeatedly without damaging the final product, in which the segmented structure was never intended to be disguised." It is important to note that none of Close's images are created digitally or photo-mechanically. While it is tempting to read his gridded details as digital integers, all his work is made the old-fashioned way - by hand. Close's paintings are labor intensive and time consuming, and his prints are more so. While a painting can occupy Close for many months, it is not unusual for one print to take upward of two years to complete. Close has complete respect for, and trust in, the technical processes - and the collaboration with master printers - essential to the creation of his prints. The creative process is as important to Close as the finished product. "Process and collaboration" are two words that are essential to any conversation about Close's prints.

PUBLICATION EXCERPT FROM DEBORAH WYE, ARTISTS AND PRINTS: MASTERWORKS FROM THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK: THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, 2004, P. 238.

Chuck Close is celebrated for his monumental portrait paintings in which sitters stare out at viewers with uncompromising gazes. Although identified by name, these subjects reveal none of the nuances of individual personality found in traditional portraiture. Instead, Close focuses on his working procedures—the "means" rather than the "ends" usually associated with this genre.

It is the visual effects of translating a photograph into a painting that Close exploits in endless permutations. Translating still further into printmaking offers even more variables to stimulate his creativity. He has completed approximately fifty-five prints, working in numerous techniques. These editions have allowed a broad audience to have access to his work, a fact that Close appreciates since his painting process is lengthy and results in relatively few canvases.

Close's active engagement in printmaking began with his first print, Keith/Mezzotint, created in 1972. This project came about at the instigation of publisher Robert Feldman of Parasol Press, who arranged for Close to work with master printer Kathan Brown at Crown Point Press. So as not to be intimidated by the printer's expertise, Close rather perversely selected mezzotint, a long-out-of-favor and laborious technique that would be as much of a challenge for Brown as for him. When his constant trial proofing wore down the markings on the plate around the mouth, Close decided he liked that exposure of his process and went even further by allowing his grided guide to show through. From that time on, a grid has often been visible in his work in all mediums. Such fruitful collaborations with printers, and the impetus of invigorating new techniques, have repeatedly fed back into Close's work as a whole and made printmaking essential to his overall artistic practice.

In 1988, Close was diagnosed with a rare spinal artery collapse, which he refers to as “The Event,” and has been forced to paint in a wheelchair ever since. However, his artwork has evolved to accommodate his new circumstances, incorporating pixelated squares of color, which he paints with a brush strapped to his wrist, and which, from far away, create the effect of a unified composition.

Close lives and works in New York City and Long Island.

-

Holiday Group Exhibition

Gallery Reception: December 7th, 1-4 PM 7 - 31 Dec 2019Dawson Cole Fine Art Gallery is proud to present a Holiday Group Exhibition featuring works by Richard MacDonald, Jian Wang, Tom Betts, and Jim Lamb. Join us for a festive...Read more -

Beauty of Line & Form

Gallery Reception: August 3rd, 1-4PM 3 - 31 Aug 2019Since the time of Plato the concepts of Beauty and Truth have been wedded in Western thought. We intuitively know that there is a difference between a pleasing surface beauty...Read more -

Turning Heads

A Group Exhibition: Chuck Close, Jian Wang & Richard MacDonald 9 Jun - 1 Jul 2018Turning Heads: A Group Exhibition . The face, recorded through the eyes of the artist, truly lives forever. Portraiture has been central to the history of art for centuries and...Read more